Forget the stereotypes - celebrate Essex's radical past

Modern Essex is a county of two halves – divided by the A12 into the affluent north and the post-industrial south.

The less-privileged half, once the stronghold of unionised labour in the docks, the motor industry and industrialised Thameside, has become synonymous with the Right – the home of Basildon Man, the heartland of UKIP and the nihilism of The Only Way is Essex, the TV series that charts the loves and jealousies of the young, under-educated residents of Brentwood and Buckhurst Hill.

The rest of the county revels in its rural heritage – small market towns and villages separated by rolling agricultural land.

It is also the county’s radical heritage – of upstart freemen, millenarian priests, oppressed agricultural workers and anarchist communities.

This long and rousing radical history is glossed over in media representations of the county, which overlook the sometimes short-lived utopian communities across the county in the nineteenth century, inspired by the anarcho-Christian aestheticism of Leo Tolstoy.

The Peasants’ Revolt

Experiments such as these could never tackle the social problems caused by the decline in agriculture and the associated poverty in rural areas. But their tone invoked the spirit of John Ball, the Colchester-based priest who preached across Essex in the period immediately before the Peasants’ Revolt.

Preaching in English rather than the Latin of the established church, Ball spoke out against the practice of bondage, which, allied with the hated poll tax, was a major cause of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.

And it was in Essex that the first act of the revolt occurred on May 30, 1381, when a Court officer seeking to collect unpaid tax was violently by rebels from Fobbing, resulting in several deaths, including three of the officer’s clerks.

The uprising spread rapidly across the south-east, with rebels burning court records and opening the local gaols.

Ball was one of many to be freed from prison. As rebels from Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk marched on London, Ball spoke to some of them on Blackheath, and is attributed with one of the earliest and lyrical expressions of socialist ideology:

“When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman? From the beginning all men by nature were created alike, and our bondage or servitude came in by the unjust oppression of naughty men.

“For if God would have had any bondmen from the beginning, he would have appointed who should be bond, and who free. And therefore I exhort you to consider that now the time is come, appointed to us by God, in which ye may (if ye will) cast off the yoke of bondage, and recover liberty.”

With the death of Wat Tyler at Smithfield, the end was in sight for the rebels. The retribution was severe, with the leaders of the revolt and their foot soldiers being shown no mercy.

Ball himself paid for his beliefs with his life: hanged, drawn and quartered at St Albans on July 15, 1381, in the presence of King Richard II.

The Tolpuddle Martyrs

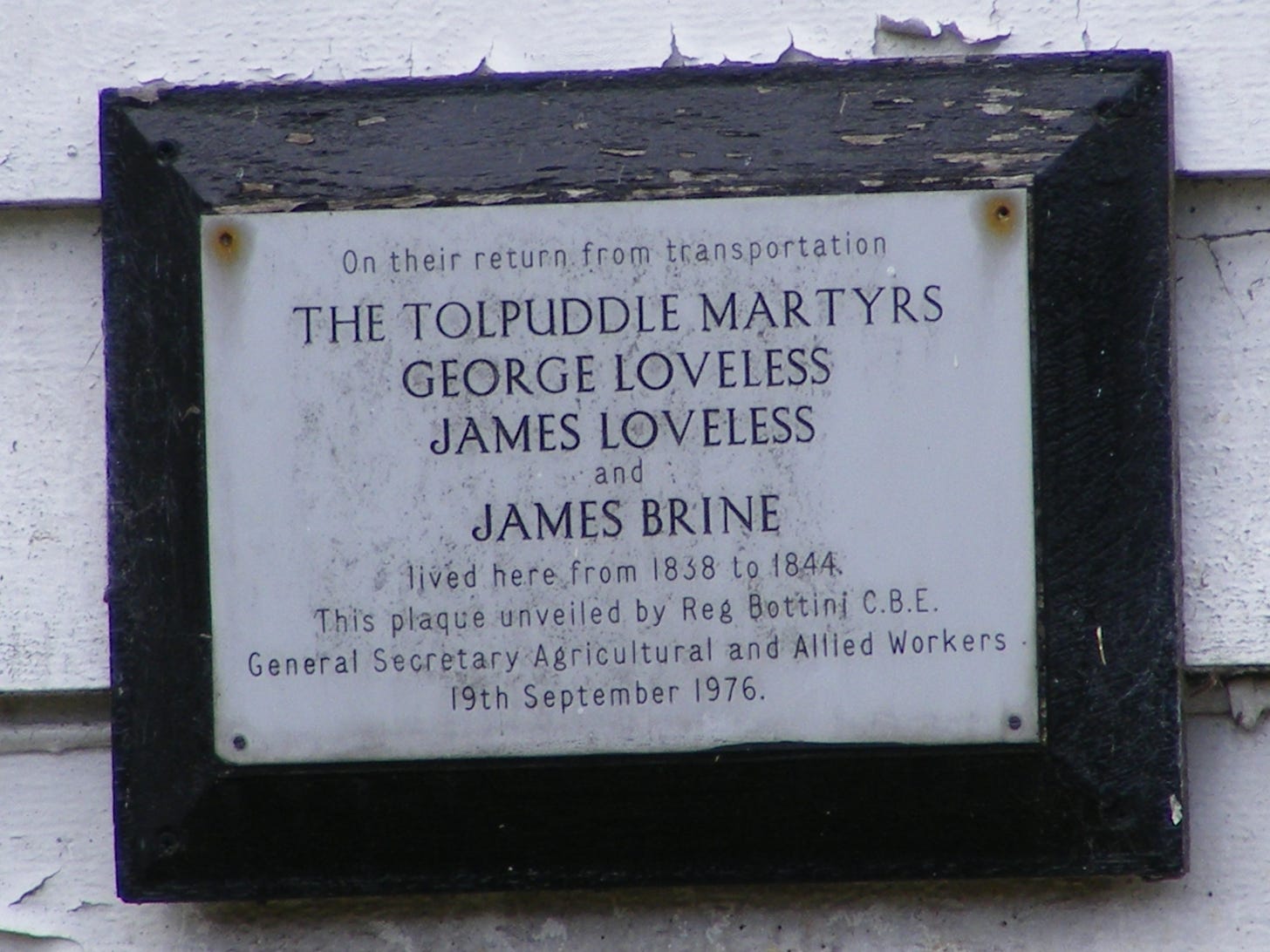

The Tolpuddle Martyrs are principally associated with Dorset. But, after the populist campaign to end their exile in Australia, three of the martyrs, George Loveless, James Brine and the Standfield family, returned to Essex in 1837-38. The London Dorchester Committee raised funds with public support to buy leases on farms in Essex for the returning martyrs, who continued to campaign for working men’s rights under the red, white and green Chartist banner.

The Chartist cause

They organised a Chartist association in Greensted, following the six points of ‘The People’s Charter’: Manhood Suffrage, Voting by secret ballot, Payment of MPs, Annual Parliaments, Abolition of property qualifications for MPs Equal electoral districts. There was a predictable reaction from the Essex squirearchy and the Church. The Vicar of Greensted accused them of undermining the foundations of decent society and alerted the Home Office.

The Essex Standard stated: “George Loveless, instead of quietly fulfilling the duties of his station, is still dabbling in the dirty waters of radicalism and publishing pamphlets to keep up the old game.”

Seven years after first arriving in Essex, five of the Martyrs emigrated to a freer life in Canada. A plaque commemorating the Martyrs’ time in Essex can be seen on the wall of Tudor Cottage – part of what was New House Farm.

Tudor Cottage, Greensted Green, once part of New House Farm

It was a sensible move. In the 19th century agriculture was entering a long period of decline, with bankruptcies among farmers escalating, hitting their workers hard.

Farmworkers organise

Their response was to organise – but not to improve wages. The National Agricultural Labourers Union in the county promoted migration to the northern industrial towns, where farm workers became unskilled labourers. When migration turned to emigration, resistance grew and union leaders backed their members in the great lock-out of 1874. But the union had to concede defeat, with the effect that more radical forces came to the fore.

In June 1914, the first agricultural strike in Britain was called, with the village of Ashdon, near Saffron Walden, at the forefront of the fight for an increase of six pence a week. The strikers struggled to survive on strike pay and suppression was harsh – eight farm workers from Ashdon were given a month in Cambridge jail. An agreement giving the union a modest victory was finally reached just one day before the outbreak of war.

The events would not have passed unnoticed in nearby Thaxted, where the Rev Conrad Noel had become vicar in 1910. Noel continued in Ball’s radical vein, becoming a founder of the British Socialist Party, which was one of the progenitors of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Noel, known as the Red Vicar of Thaxted, famously hung the red flag and the flag of Sinn Féin alongside the flag of St George in the church until ordered to remove them by a consistory court. During his tenure a tower chapel was dedicated to Ball.

Superficially rural Essex is a bastion of privilege with industrial farmers living alongside City folk who find a country existence relatively close to London appealing. There are fewer agricultural workers now, reflecting the virtual disappearance of labour-intensive dairy and mixed farms and their replacement by industrialised arable farming supported by sophisticated technology and contract labour.

Just as the anarchist settlements have long disappeared, the last vestiges signs of a more recent radical presence in the county, Communist Youth Camp on the edge of the Essex village of Kelvedon Hatch have finally disappeared.

Known to older village residents as the Coppice Camp, the Harry Pollitt Memorial Youth Camp, named for the Communist Party’s long-term general secretary, was bought by an East End doctor in the late 1920s or early 1930s. Dr Carl Cullen, who practiced in the East End slums of the inter-war years, had a strong belief in fresh air and exercise. He was initially active in the Scouts, then in Kibbo Kift, and ultimately the still-extant Woodcraft Folk.

Originally a member of the Independent Labour Party, he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain in the mid-1930s, when awareness of the menace of Nazism was growing. He offered Coppice Camp to the Young Communist League and it quickly became a weekend meeting place for left activists, many of whom lived in London’s East End.

As well as summer camps for the YCL, the party made use of the campsite as a venue for weekend schools. Volunteers for the anti-Franco International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War received early training there.

Campers were allocated accommodation in a number of huts, at least one of which has only just been demolished.

During World War Two, the camp was requisitioned to house six families bombed out of the East End.

Activities resumed after the war, with political education classes as well as walking and other outdoor activities. After Dr Cullen’s death, ownership passed through the Communist Party to a trust with CPGB members, including Jimmy Reid of Upper Clyde Shipbuilders fame, as trustees.

A development programme began, including acquisition of a green traveller-style caravan, which remained visible through the vegetation for many years after the camp closed.

The caravan and some tents donated by a visiting Czech delegation provided additional accommodation from the mid-1960s onwards.

A distinguished visitor in 1969 was Peter – now Lord – Hain, who spoke about the ultimately successful campaign to stop the all-white South African cricket team from touring England

In 1981 a bungalow next to the camp – now awaiting development – was sold to then its occupants who had acted as camp caretakers and whose family owned the bungalow until recently.

During its final years of operation the camp was used to provide holidays for the children of striking miners during the 1984-85 strike. It was also used by the party’s travel company, Progressive Tours, to accommodate holiday groups from the former Soviet Union and other socialist countries, not entirely without complaints from the visitors about its locality and condition.

Finally, in 1991, the party sold the camp for just under £69,000, ending nearly 70 years of association between revolutionary socialism and an otherwise unremarkable Essex village.

It is to Essex’s rural past that progressive forces – and there are some in the county – need to turn their attention to ensure that younger rural residents’ futures are not blighted. But in most communities, no matter how prosperous, there are residual pockets of rural poverty, of older people left behind by the rapid changes of the second half of the 20th century, and of younger people marooned by the absence of workable transport links and limited job opportunities.

They too deserve a positive future in the spirit of hope and progress.